Respected Tampa lawyer and art collector Robert “Pancho” Sanchez is examining beach life through the eyes of artists from the World War II era

As a young boy, Robert Sanchez spent much of his days on the Atlantic Ocean along Satellite Beach, a barrier city in Brevard County, trying to catch the perfect wave. With his father stationed at Patrick Air Force Base after a tour in Vietnam, most of Sanchez’s childhood revolved around the ocean, taming rip curls and snapping photos of surfers.

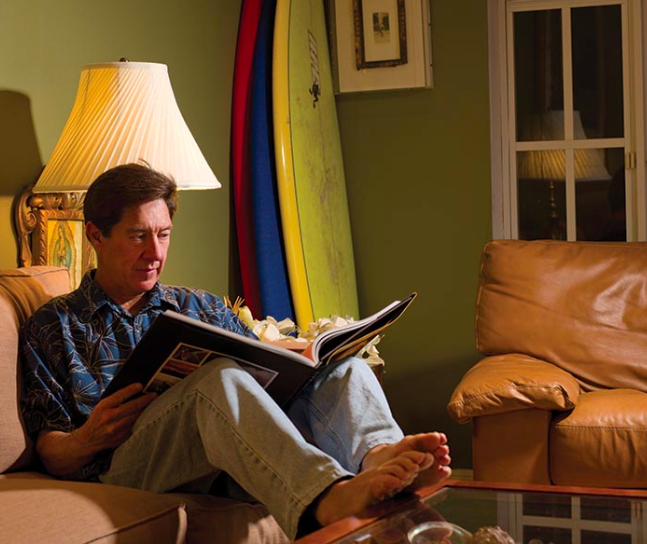

The well-respected art collector from Tampa—who also goes by Pancho—is enamored with beach culture and amassed hundreds of surfing magazines as a kid. He explains this while sitting on a living room chair in his South Tampa home one January afternoon. Dressed in conservative attire—slacks and a button-down shirt sans tie— he has just returned from his office at McNamara & Carver, where he’s a corporate lawyer. Known for assembling expression prints and photos, his collecting has become more purposeful since his teenage years, but even as Sanchez approaches the age of 60, he still has that laid back surfer outlook on life.

To Sanchez, the beach represents dreams and a horizon that’s endless. Some say the ocean is in our blood and that everyone returns to it instinctually.

In the U.S., more than one-third of the population lives on the coast and the vast majority live within a four-hour drive of the shoreline. As that number continues to grow, what was once known as a place of work has faded into a place of leisure and luxury, says Sanchez.

This fascination for imagery and history has inspired him to explore artistic interpretations of the beach from the 1930s and 40s. His goal: to show the variations and styles of how coastal life has been portrayed over the years.

“This country was founded by people coming to the shores so it holds that metaphysical connotation,” Sanchez says. “And when it comes down to it I want to collect the imagery that will tell that story.”

***

To fully understand his enthusiasm for humanities you must go back to when Sanchez was a fine arts major at the University of Florida who dreamed of being a renowned painter. He eventually realized that artists are typically referred to as “starving” for a reason, or so his grandmother reminded him. So he applied for law school after graduation in 1981. He didn’t get his first taste of art collecting until he took a job at Trenam Kemker Attorneys in Tampa, where he learned how to collect thematically as a member of the collecting committee.

He stayed there for several years until leaving in the early ‘90s to travel the world with his wife, Elizabeth, and search for photographs and other art from Vietnam and Cambodia, specifically the areas surrounding the Angor Wat temple. Upon arriving home in 2003, Sanchez made his first attempt at exhibiting art with Sacred Space: Angkor Wat in 19th and 20th Century Photography, a St. Petersburg Museum of Fine Arts exhibition that featured images covering 140 years in the area.

Sanchez followed up that exhibit with Turmoil and Triumph, another Museum of Fine Arts exhibit that showcased his archive of prints produced in the years that led up to and during World War II. With more than 70 prints made by Works Progression Administration (WPA) artists who received federal grants to document the war, Turmoil and Triumph was the apex of Sanchez’s collecting career.

“Most collectors collect multiple things happening at the same time. But to me, collecting is a way to tell a story and I believe that if you do it correctly the sum is greater than the continuation parts and you’ll tell a narrative through a disparate collection of images,” he says.

For Sanchez, collecting art is a “serendipitous search” to satisfy his own curiosity. It’s about acquiring the knowledge to recognize a treasure that perhaps someone else doesn’t. The search for art from the WPA era opened a door that led him back to the beach. And over the last few years, he has collected a series of prints that show varied interpretations of how the world sees one of Florida’s greatest natural resources.

***

In between riding waves in Cost Rica, Puerto Rico and Florida’s eastern coast, Sanchez is actively scouring galleries, auctions and independent sellers for prints that build his tale of two beaches. He has noticed discrepancies in how artists from the 1930s envisioned the beach, with a collective impression of fisherman, farmers and the occasional surfer. His series of 12-15 serigraphs, or screen prints, show the variations in how coastal life was once documented.

“These artists have something to say and their imagery is fused with that emotional conviction,” he says.

When he’s finished, which could take years, Sanchez hopes to exhibit his pieces in the Samuel P. Harn Museum at the University of Florida. Unlike the hectic life he leads in the courtroom where time rules supreme, this beach bum turned collector is enjoying the thrill of chasing down these pieces of history, even if it does take him years to do it.

“That’s the most enjoyable part, the hunt and the research,” he says. “With collecting, I believe that the most valuable resource a collector has is time, it’s not money. A museum or a gallery, they have time constraints. But as a private collector, you have the luxury of time. There’s no pressure on you so you can take as long as you want, until the amount of imagery has reached critical mass.”